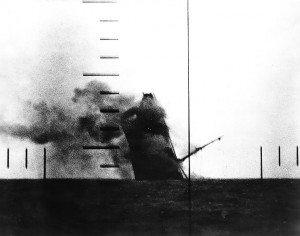

The sinking of HMS Culloden

“……The ship shuddered and heeled violently, pitching Lindsay forward on to his hands and knees. Thin blue smoke was rising from the starboard side below the funnel, ragged chunks of steel falling through it like a fountain. The wireless mast, the bridge and fo’c’sle were toppling to starboard and above the wail of the Atlantic Lindsay could hear the screech of grinding metal. Someone at his shoulder was moaning, ‘Please God no, please.’ Then it was over, over in a terrifying, bewildering instant. The entire forepart of the ship had gone and with it close to two hundred men. Through the spray and smoke, Lindsay could see the for’ard section drifting away, the dark outline of stem and bow uppermost, the bridge and most of the mess deck beneath the waves. A torpedo had torn the ship in two and men he knew well were struggling below against a dark torrent. He could see them there, a savage kaleidoscope of images, but he could do nothing to help them……”

Lt Douglas Lindsay is caught in the blitz on Liverpool in May 1941

“…..The rude clatter of hobnailed boots on the steps dragged Lindsay back to the rumbling, shuddering world of the shelter. The door opened, the blackout curtain was brushed aside and a small boy in pyjamas and a coat was gently propelled across the threshold. He was followed by a burly fireman with a smoke-stained face: ‘Room for one more? Found this little bugger in the street on his own.’ There was a good deal of clucking and fussing as the boy was settled with a blanket and a biscuit. Someone handed the fireman a canteen of water and he emptied it without pausing for breath. ‘What’s it like out there?’ asked Lindsay’s rescuer, George Barnes. The fireman wiped his chin with a dusty sleeve: ‘The city’s on fire. Hell, that’s what it’s like, hell.’ He seemed remarkably cheerful for one who had just escaped from the other side. ‘Lewis’s Store, Kelly’s and Blackler’s – a couple of the Navy’s ships are on fire, I was on my way there . . .’

On an impulse, Lindsay got to his feet: ‘I’ll come with you.’ The fireman turned to look him up and down. ‘Why? You’d best leave well alone.’

‘I don’t want to sit here. Let’s go.’ He pushed past the fireman to the door and stepped through it into a strange flickering half-light. The sky was the colour of a blood orange and smoke was rising thickly as far as the eye could see. He could feel the heat on his face and hands and small pieces of burnt paper swirled about him like leaves on an autumn day. A gas main had been hit and a jet of yellow flame was rising from the pavement like a geyser. At the end of the street, a four-storey building was burning fiercely and on the road in front, half buried by bricks and charred timber, a naked body, stiff and white. It was a sickening sight. Lindsay could not tear his eyes away. He took an uncertain step closer and relief began to wash through him: it was a dummy, just a shop’s dummy.

The fireman was tugging at his arm: ‘We’ll have to go this way.’

They set off down a side street at something close to a trot, their boots crunching across a carpet of broken glass and slate.

It was only a short distance to the river. Strand Street was a shambles.

The front of a large warehouse had collapsed, spewing masonry across the road and exposing the blasted shell behind. A clanging ambulance was weaving uncertainly towards the quay where a thick pillar of acrid black smoke was rising from within the great brick walls of the outer dock. A short distance away, half a dozen exhausted firemen were standing round their engine waiting for instructions.

Lindsay’s companion roused them with an angry stream of four-letter words. High-explosive detonations flashed and rumbled down the river; people and history were being wrenched from the streets of the city…..’

Lindsay interrogates the young U-boat officer, August Heine

“The interrogation rooms were on the same floor in the west wing of the house. A couple of bored-looking guards were posted at the door of Number Three. Lindsay stood between them for a few seconds, breathing deeply, then he reached for the handle and walked inside. A draught of cold air swept into the room with him, stirring the cigarette smoke above the table.

Brown glanced over his shoulder: ‘What is it?’

Lindsay said nothing but pulled the door to with a heavy clunk and leant against it, arms folded. Brown was half out of his seat, a dark frown on his face: ‘What on earth . . .’

‘We’re going to blow hot, blow cold,’ said Lindsay calmly.

‘What?’

‘Just sit down.’

He looked across at Heine and said in German: ‘Herr Leutnant, you are going to tell me everything you know about your commander – Kapitän zur See Jürgen Mohr.’

Heine shook his head slowly.

‘Oh yes you are,’ said Lindsay coldly. ‘I know he was on the staff at U-boat Headquarters.’

Heine gave another nervous shake of the head.

‘Don’t deny it. I know. And I’m sure Kapitän Mohr would like to know how I know.’

Silence. Heine knew he was being threatened, but with what?

Then his shoulders dropped and he crumpled over the table, his face in his hands.

‘Not me.’ His voice was shaking.

101

Unfolding his arms, Lindsay walked to the edge of the table and leant across it until he was only a foot from him:

‘Look at me, Herr Leutnant. Look at me. It was you. You know it was.’

‘I . . . please . . .’ He was very frightened.

‘Tell me and he will never know. But you must tell me, tell me now.’

Heine was hugging himself, rocking to and fro on his chair, close to tears.

‘Herr Leutnant, tell me at once.’

It was an order.

‘I can’t . . .’

‘Was Kapitän Mohr on Admiral Dönitz’s staff?’

Heine said nothing but gave the slightest of nods.

Is that yes?’

‘Yes.’”

August Heine is tortured by fellow U-boat officers in the POW camp kitchen

“‘……We should hang the bastard.’

‘No, the bastard should hang himself. He would if he were any sort of man.’

And someone yanked the rope beneath Heine’s chin, dragging his head from his chest.

‘There’s a meat hook in here. String the bastard up from the ceiling.’

The rope cut deeper. Heine’s lips were drawn tightly over his teeth and he gasped and whooped for air, his hands tearing at the noose.

And in his tortured face there was a desperate plea for help. He seemed fl eetingly to look at Lange, beseeching him, begging, ‘Please, please.’

‘Stop it. Stop it.’ The words came to Lange at last, breathless and shaking with tears. ‘Let me help him.’

But someone was holding him down, twisting his arm behind his back. It was his room-mate, Schmidt.

‘Shut up,’ Dietrich barked and he pushed his face close to Lange’s. ‘Why do you want to help a traitor?’

They were all looking at him now, angry that anyone should dare to challenge their justice with a show of pity.

‘Why? You of all people.’ Lange could feel Dietrich’s hot stale tobacco breath on his cheek. His blue eyes were mad with anger, the pupils fully dilated. Slowly, he reached up and pinched Lange’s left cheek between his thumb and forefinger, digging his nails in hard until he gasped with pain.

‘You’re lucky it’s him,’ Dietrich hissed.”

Lt Commander Ian Fleming speaks to Mary Henderson about Lindsay

“A group of crisply dressed Staff officers had just left the Director’s office and were chatting noisily at his door. Mary slipped past, head bent, anxious to catch no one’s eye.

‘Dr Henderson . . .’

It was the Director’s Assistant. She turned to greet him:

‘Ian, how are you?’

Fleming reached for her hand, then kissed her warmly on both cheeks: ‘Lovely, even in your customary academic dress, and do you know, I was just thinking of you.’

Mary raised her eyebrows sceptically. She had known Ian Fleming since childhood, an old family friend who had been at Eton for a time with her brother. But he was an adventurer – fine words had been followed more than once by a direct challenge to her virtue. A handsome thirty-three, Fleming was tall, immaculate, with wavy hair, tired close-set eyes, a strong jaw and a severe mouth that turned down a little disdainfully at the corners. She had always stoutly resisted his attempts to seduce her – that was why they were still on good terms. ‘I’ve just left the Director. We were talking about your chap.

Your name was mentioned too,’ he said, squeezing her hand gently between both of his.

Mary coloured a little and slipped free: ‘Why on earth . . .’

‘It isn’t a secret, is it? Don’t academics take lovers?’

‘Only sensitive ones.’