Preparations for a German biological weapons programme seem to have begun at the beginning of 1915. The General Staff considered the infection of horses and other livestock an attack on military supplies and a legitimate act of war. Dr Anton Dilger travelled with cultures of both the anthrax and the glanders baccilli in September 1915 and set up his laboratory on the outskirts of Washington, much as I relate in The Poison Tide. He made a further trip to the United States the following year with more of the cultures. There is no evidence Dilger and his associates were intending to attack Allied soldiers or civilians, only the horses, mules and cattle they needed for the waging of the war on the Western Front.

Mules at the Front

The biological warfare programme grew in scope and reach with agents operating not just in the United States but against Allied interests in Romania, Spain, Norway and South America too.

We now know the German General Staff did consider using biological weapons against soldiers and civilians. On 7th June 1916 the naval attaché in Madrid, Commander Krohn, sent a telegram suggesting the contamination of rivers with cholera bacilli, but his proposal was rejected. A few months later the Staff was presented with another. A military doctor, Oberstabsarzt Winter, argued the dropping of plague bacilli from zeppelins on English ports would infect local populations and cause general panic. The idea seems to have interested the new Chief of the General Staff, General Ludendorff, but it was categorically ruled out by the Surgeon General. ‘If we undertake this step’, he wrote, ‘we will no longer be worthy to exist as a nation’.

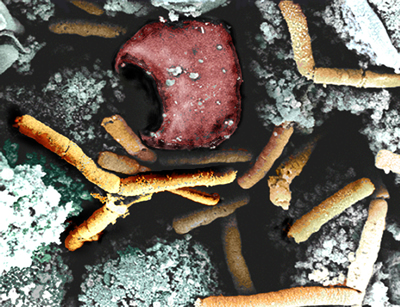

The tissue of a monkey with inhalation anthrax. The rod shaped bacilli are yellow

There were many rumours of German biological attacks on both allied soldiers and civilians. In 1917 the British Home Office instructed the police to take precautions against anthrax. A few months later civil servants reported information from a French source, ‘that the enemy had inoculated a large number of rats with plague, and they intended to let them loose in the United Kingdom from submarines and aeroplanes’.

Culturing then infecting the animals required more effort than many German agents were prepared to make. After the war, scientists in Britain and elsewhere were able to mill anthrax spores to something like a dust that could be used more effectively in a high explosive device and it is still regarded as one of the most potent biological threats.

The accidental release of anthrax spores from a weapons facility in Sverdlovsk in the former Soviet Union in 1979 resulted in 79 cases of anthrax infection and 68 deaths. Scientists are particularly concerned about the release of spores in an aerosol by a terrorist group or in a dirty explosion. Colourless and odourless the spores might travel many miles before disseminating. In 1993 a report by the US Congressional Office of Technology Assessment estimated the release of 100 kilograms of anthrax spores upwind of Washington DC would result in anything from to 130 000 to 3 million deaths – a death rate that matches the impact of a hydrogen bomb on the district.