From the first, the new Secret Service Bureau devoted a great deal of time and thought to the ‘tradecraft’ of the spy. The ‘chief’ set an example. Cumming worked hard at perfecting his own disguises, visiting a renowned London theatre makeup artist for assistance with paint and his toupee. For a meeting with a contact called ‘Ruffian’ in January 1913 he arrived in a taxi. The best method, he noted, for ensuring the contact couldn’t point ‘you out to his friends, who may be waiting with a camera’. The trick was to ‘drive past the rendezvous on the opposite side’ and when the target was spotted, ‘drive up close to him, open the door and invite him in. I lean back at the moment I have caught his eye, and from then onwards do not show myself at all.’

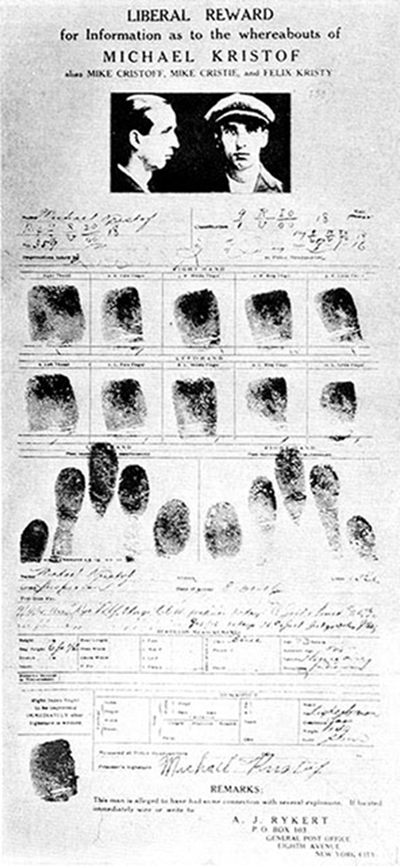

Wanted poster for a German Agent

A great deal was learnt from trial and error in the field during the First World War, the sum of the Bureau’s collective wisdom captured in 1918 in a 135 page manual entitled ‘Notes on Instruction and Recruiting Agents’ that dealt with codes, secret inks, the forging of documents, letter boxes – locations where secret messages could be left – sabotage, cover and the infiltration of foreign intelligence agencies. The first commandment: ‘Don’t get cold feet, but if you do get caught, keep your mouth shut and don’t give anybody away’. An agent should never use his or her real name or write to contacts – type – and never keep a copy of the signal. Agents were reminded of the case of a German agent working in Britain who was traced from a carbon found on one of his comrades: he blew his brains out to avoid arrest. By 1918 experience had taught that one of the best sort of covers for an agent was ‘commercial traveller’, but it was a ‘hopeless business unless the agent really knows and understands the article he is supposed to sell and also really transacts business in such article’. Spies were also advised to have at hand ‘an efficient highly technical expert burglar’.

Agents resorted to the usual time honoured methods of coaxing with bribes and coercing with blackmail.

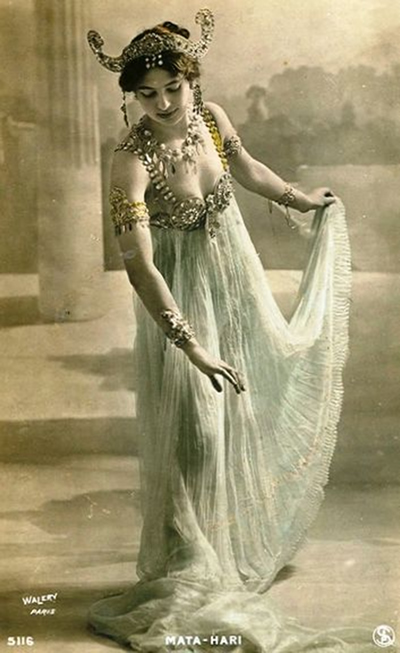

The ‘exotic dancer’, Mata Hari, managed to entice a procession of Allied military men – general to lieutenant – into her bed, but was unable to glean any intelligence of real value to her German paymasters. The British Agent, Norman Thwaites – a character in The Poison Tide – described a ‘honey trap’ he laid in New York for the military attaché of a neutral country who ‘patronised young ladies of the chorus’; ‘it was not a difficult matter to bring to his notice the charms of an intelligent young woman in the front row of a musical comedy at the theatre – the bait proved instantly attractive and the poor fish was hooked’. Thwaites admits the success of his scheme made him wonder if he too had been ‘a victim of some delectable female’.

The British Agent’s best friends behind enemy lines were the locals who offered their services, not for payment but for love of their country, everyone from the old lady who sold her vegetables at the market in the Belgian town of Roulers who acted as a Secret Service courier, to signalmen, shop keepers, priests and prostitutes who offered intelligence on the movements of German military units to the Front.

British Agents required no licence to kill. When the German occupied Brussels they took over a powerful wireless transmitting station and employed a young student, Alexander Szek to repair it. One of the Bureau’s agents was able to persuade him to make copies of a German codebook. But in the spring of 1915 Szek’s nerve began to fail. Concerned he would breakdown down to his German masters, an assassin was paid a £1000 for his liquidation.

Cumming was fascinated by the technical side of espionage, encouraging research into wireless communications, covert listening devices, coding and telephone tapping. Concealed cameras like the Tika were available to Agents and the requirement for telephone calls to pass through an operator presented plenty of opportunities for ‘eaves dropping’.

Both sides put a great deal of effort was put into bespoke explosives. The German spy, Franz von Rintelen – another character in The Poison Tide – commissioned an incendiary – the ‘cigar’ bomb – that burnt so hotly it destroyed the evidence the fire was an act of sabotage.

German bombs seized by police in America.