The blackmailing of a Prime Minister, a secret service conspiracy to bring down an elected government: the Establishment fears of a Russian style revolution after the First World War that form the backdrop to The Prime Minister’s Affair.

The old county town of Brecon is not a place you would expect to find Communists calling for workers to unite and rise in a Russian style revolution. A quieter place now than it was after the First World War when it boasted a working canal and a railway to the coal and iron valleys of South Wales, and yet a rural backwater even then. A pretty town of six thousand people, with a cattle market, a cathedral, painted Georgian houses – and a barracks.

The barracks, Brecon

It was at the gates of the barracks on the 25th of May 1930 that two unemployed workers from Dowlais presented themselves with the intention of distributing leaflets to the men of the South Wales Borderers. Their appeal was for class solidarity with Indians ‘fighting for bread and national freedom’. If the ‘imperialist’ British government sent men of South Wales to India they were to refuse to shoot heroic workers and peasants campaigning for their freedom. Instead the Soldier-Comrades were to turn their guns on their ‘real enemy – the thieving, robbing, British ruling class’.

Distributing leaflets outside the barracks home of a regiment famed for its part in suppressing colonial risings in India and South Africa was by any estimation a foolhardy thing to do. But the Communist Party was struggling to break down the barrier between ‘workers in uniform’ and workers in factories and pits. Party members had tried in other garrison towns and had been arrested and fined for ‘insulting behaviour’ – the Dowlais men were to meet a much a harsher fate.

For most of the twentieth century Britain and Russia were engaged in a low level war. In the years following the defeat of Hitler’s Germany in 1945 it was the Cold War nuclear stand off with the Soviet Union. But a propaganda war, a war of espionage and subversion had begun even earlier with victory over the Kaiser’s Germany in the First World War. What did victory mean if not jobs and better living conditions, a vote for working men and women who had sacrificed so much? British trade unions demanded the country’s war time leaders honour their pledge to build a land fit for heroes, and some of their members looked east for inspiration – to the new workers’ state, the Soviet Union.

In January 1919 – three months after the armistice that ended the war – thousands of Clydeside workers protested in front of Glasgow City Chambers in support of a forty hour working week and a Red Flag was raised in the centre of the crowd.

Red Flag raised in Glasgow January 1919

Panic ensured, the Riot Act was read, and the police waded in with their truncheons. The Secretary of State for Scotland advised his Cabinet colleagues that it was a Communist rising, and troops and tanks were sent on to the streets to restore order. ‘The plan of the revolutionary minority was to use the Clyde as the touchstone for a general strike and… achieve a revolution’, warned head of Scotland Yard’s Special Branch, Basil Thompson. The revolutionary minority he had in his sights were the British ‘Bolsheviks’ – the Communists – and the leaders of the country’s big trade unions.

Tanks on streets of Glasgow January 1919

In Thompson’s estimation ‘revolutionary feeling’ was promoted by a deep sense of injustice among those who had made sacrifices to win the war. In particular he cited resentment at profiteering and high prices, bad housing and class hatred of the rich. ‘Every act of foolish ostentation on the part of the well-to-do is fuel to this smouldering fire’, he noted.

But Conservative politicians and senior intelligence officers were in thrall to the spectre of the ‘Red Menace’, the threat posed by the Soviet Union and fear of a Communist revolution in Britain. Communist and trade union leaders were arrested, the Party’s headquarters was raided and ransacked, and its meetings were broken up by ‘casual’ agents working indirectly for the intelligence services. Suffragette, Sylvia Pankhurst, was among those arrested and sentenced to six months imprisonment for publishing seditious articles. The influence of Communists in the Labour Party and the unions was of particular concern to the secret services, and they greeted the election of a minority Labour government in 1924 with dismay. Not only had members of the new government been placed under surveillance during the war, but MI5 had recommended the prosecution of the new Prime Minister, Ramsay MacDonald, for making seditious speeches.

Labour leader, James Ramsay MacDonald (centre)

Labour’s politics were by no means revolutionary, but that was how senior Conservative politicians, their friends in the Press and the secret services chose to view them. Winston Churchill described the election of the Labour government as a ‘national misfortune such as has usually befallen a great state only on the morrow of defeat in war’. And from the first, senior members of MI5 and MI6 were, in the judgement of the official Foreign Office historian, not only ‘waiting for it to make a mistake, but also working to undermine it in any way possible’.

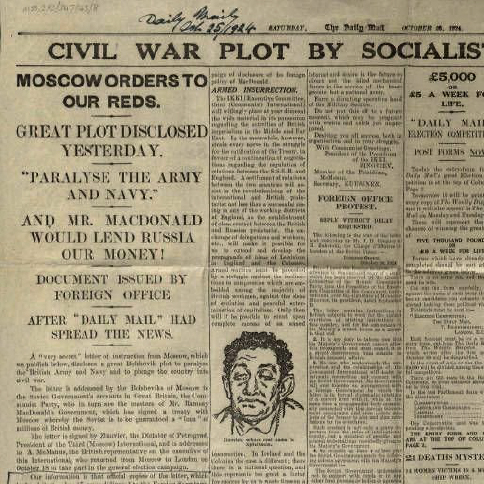

Their opportunity came four days before a second general election in 1924. A secret letter purporting to be from Soviet leader, Grigori Zinoviev, found its way from the intelligence services to the Conservative Party and the Daily Mail. The letter called on British Communists to subvert the loyalty of soldiers and sailors in preparation for an armed rising in working class districts. Civil War Plot by Socialists’ Masters: Moscow Orders to Our Reds, was the headline in the Daily Mail. The paper’s readers were encouraged to believe Labour was doing the Kremlin’s work. The rest of Fleet Street waded in, and four days later Labour was soundly defeated in the election. Lord Beaverbrook, the proprietor of the Daily Express, congratulated Lord Rothermere, the proprietor of the Daily Mail, on his ‘red letter’ scoop. The paper had won the 1924 election for the Conservatives and saved the country from a socialist revolution, he declared.

Daily Mail, 26 October 1924

No matter the letter a forgery, it had done its job. The intelligence officers responsible for the leak were raising the spectre of a class war to undermine the Labour Party, and they succeeded. Labour was ‘the enemy’, according to one of the senior MI5 officers involved, because the ‘revolutionary tail wags Labour’s dog’.

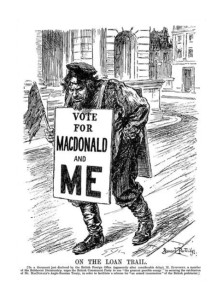

Punch caracture of a Russioan revolutionary, October 1924

With the enthusiastic support of the new Conservative government the intelligence services stepped up their campaign against the ‘Red Menace’. Agents working for both MI 5 and MI 6 burgled the Communist Party’s offices, ransacked the homes of its members, arrested and imprisoned twelve of its leaders. The judge advised the jury at their trial that ‘it would indeed be a bad day for the country’ if it did not find them guilty of seditious activities. The jury did as it was told. In a bizarre twist Mr Justice Swift offered to let the Communist Party leaders go if they agreed to publicly renounce their political opinions. They refused and were sent to prison. They were punished – the historian A.J.P. Taylor noted – not for anything they had done but for not recanting their political views.

Workers in Crewe during the 1926 General Strike

Security service intelligence reports pointed to the Communist Party’s influence at the top the unions, and amongst the miners in South Wales in particular. Merthyr Tydfil born Communist, Arthur Horner, was an influential figure in the local federation, and former Merthyr miner, Arthur Cook – a former member of the Party – the leader of the union nationally. Proof – in the view of secret service conservatives – that Moscow was funding a surge in militancy. Fear of the ‘Red Menace’ came to a head in 1926 when the decision by mine owners to cut the pay of their workers led to a general strike in the pits, on the railways, at docks, steel works and printing plants. More than a million and a half men downed tools and the Conservative government was obliged to call for white collar volunteers to maintain essential services. Ministers were in no doubt that the strike was being paid for with ‘red gold’ from Moscow. In reality, the leaders of the Trades Union Congress were acutely aware of how damaging accepting money from the Soviet Union would be to their cause and refused all offers of assistance.

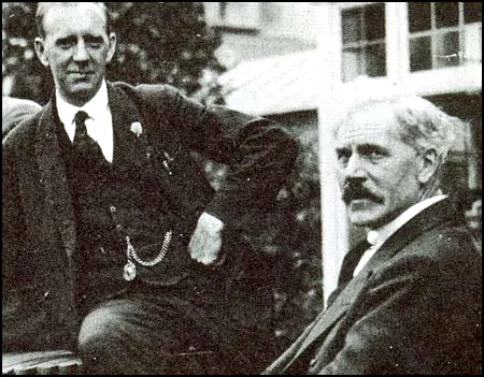

Miners’ leader, Arthur Cook with Ramsay MacDonald

Ramsay MacDonald was opposed to a general strike from the start but felt obliged to offer a public display of support. With printing works closed and newspapers off the street, Prime Minister, Stanley Baldwin, and his ministers used the recently established British Broadcasting Company to roundly condemn the strike and its leaders. MacDonald requested ‘an opportunity for the fair-minded and reasonable public to hear Labour’s point of view’, but when the BBC approached the government for permission Baldwin refused. The strike collapsed after only a few days.

In its wake union leaders recognised their best hope for an improvement in the working and living conditions of families in the South Wales coalfield and elsewhere lay not in industrial action alone but in the election of another Labour government. Labour’s leader became – in the words of a foreign observer – ‘the personification of all that thousands of downtrodden men and women hope and dream and desire… the focus of the mute hopes of a whole class’. MacDonald understood the hopes invested in him personally and that Labour would only win a general election if it was able to distance itself from Communism and the charge that it was paving the way for a revolution. Its 1929 manifesto warned electors that the Tories were trying to frighten them with ‘horrifying pictures of the disasters which would come upon the country’. ‘The Labour Party’, it declared, ‘is neither Bolshevik nor Communist. It is opposed to force, revolution and confiscation as means of establishing the New Social Order’.

Labour General Election poster 1929. The first UK election women were able to vote on equal terms with men

A sufficient number of voters were convinced to return Labour to power and Ramsay MacDonald to Downing Street as head of another minority government. His manifesto was radical on paper – aspiring to increase taxes on the rich, nationalise mines and minerals, and to take land into public ownership. Taken at face value it threatened to turn the pyramid of privilege upside down. But like most manifestos it represented a wish list rather than a practical programme for government. It frightened Labour’s conservative opponents, nevertheless, and MacDonald was under no illusions about the difficulties he would face in overcoming their opposition. ‘We have implacable enemies who sleeplessly lie in wait to damage our reputation’, he confided to his diary. Most of the senior intelligence officers involved in the Zinoviev conspiracy were still in place and their assessment of the threat posed by the Left to the security of the country and the empire remained the same.

And so it was on the 25th of May 1930 – almost a year to the day after the election of the Labour government – that Dowlais men, Arthur Eyles and John Ryan made their way to the gates of the barracks at Brecon with their leaflet. Eyles, 44, was an unemployed miner, a widower with four young children who lived on £1 12 shillings a week unemployment benefit; John Ryan, a 28-year-old unemployed labourer, married but with no children. The police were waiting and both men were arrested and charged under the 1797 Incitement to Mutiny Act with ‘maliciously endeavouring to seduce soldiers from their duty’.

The trial judge, Mr Justice Roche, described the information in the men’s leaflet as ‘extraordinarily foolish’. ‘The people of India were not ground down and oppressed’, he told the court, ‘but were protected against the periodic invasions they had experienced before, by English rule.’ So confident was he in his opinion he gave permission for the leaflet to be read in court, a decision that ensured every seditious word was printed in the Brecon County Times. Before passing sentence, Mr Justice Roche addressed the two men thus: ‘Let everybody understand’, he said, ‘I am not punishing you for your opinions, but I am punishing you for the wickedness of what you did in trying to seduce young men of impressionable age from their duty and their allegiance’. He sentenced Eyles to 12 months hard labour, and Ryan to eight. Hard to credit now but both men were sent to prison for distributing a political leaflet to soldiers the court judged too young and impressionable to form a sensible opinion, even though they were old enough to die for their country.