Number 10 Downing Street has been the property of the First Lord of the Treasury for nearly 300 years. Behind the famous black front door lies a veritable warren of offices, state and family drawing rooms. Ramsay MacDonald’s daughter, Ishbel, remembered being astonished by its rambling passages and the sheer number of its rooms. Prime Minister, Harold Wilson likened it to ‘a small village.’

Ramsay MacDonald leaving Number 10 in 1931.

As of publication, fifty-five Prime Ministers have made use of the building since its construction in the 1680s, but it is only since Arthur Balfour at the turn of the twentieth century that it has been in continual occupation as a home. Ramsay MacDonald thought little of the place at first, confiding to his diary after his second election victory that it was a great grief to him to have to move from his own house in Hampstead. Perhaps his reluctance had something to do with the uncertainty of his tenure since occupants of Number 10 can be turfed out by their party or the people with very little notice.

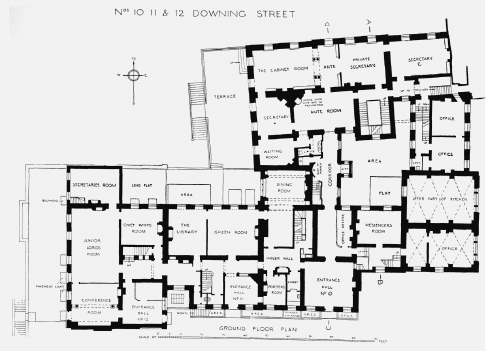

Ground Floor Plan of Number 10 in 1931

Harold Wilson’s Personal and Private Secretary, Marcia Williams, considered it ‘a dreadful place to live and work,’ but ‘an exciting place’ too. The modesty of its exterior compared to the Foreign Office on the opposite side of the street only serves to disguise the power wielded by the office of the occupant within and – in the words of historian, Peter Hennessy – ‘a deep and rich accumulated past whose resonance is such that the walls almost speak.’

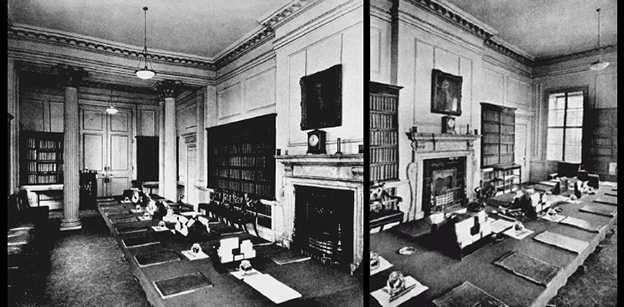

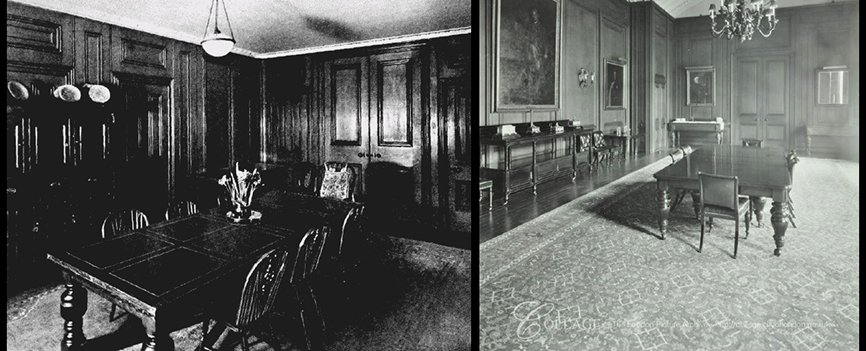

Two views of the Cabinet Room in 1927

The most famous room in Number 10 is the Cabinet Room. ‘The Cabinet Room really does know every secret,’ Prime Minister, Margaret Thatcher observed at a dinner to honour the Queen in 1985, ‘for it is there where your ministers, Ma’am, have made so many of the decision which have shaped the future.’ Lord North heard of the loss of the American colonies in the Cabinet Room; Pitt plotted the downfall of Napoleon; Lloyd George, the end of the Kaiser; and it was where Winston Churchill resolved the country would fight on alone against Hitler. Ramsay MacDonald introduced a library to the room with ministers donating works when they departed from office. Most of the books have gone today, but the portrait of the first Prime Minister, Robert Walpole, still hangs over the fireplace. Harold Macmillan replaced the table with a lozenge shape more to his liking; Anthony Eden improved the lighting; and Prime Minister Atlee banned smoking in the room.

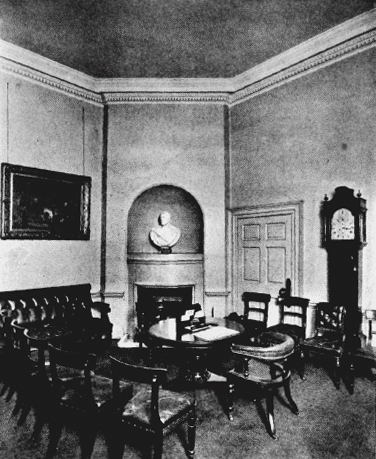

Ante Room to the Cabinet 1931

The Hall in 1927

The display of African antelope horns has gone from the hall, but the rout chairs, the leather porter’s chair and the distinctive chequer board floor tiles are still in place.

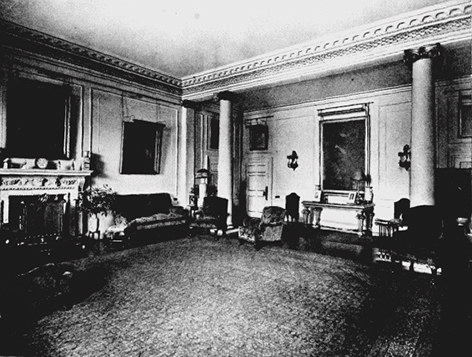

The Official Drawing Room in 1927

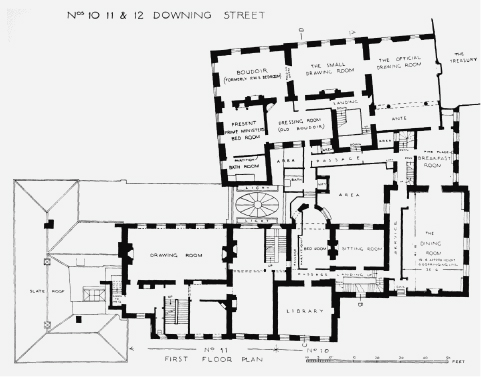

Until the 1930’s the Prime Minister lived in the State Rooms on the first floor. At the back of the house overlooking the garden and Horse Guard’s parade there was the official drawing room, a smaller family drawing room, the Prime Minister’s boudoir and his bedroom.

The Small Drawing Room in 1927

Ramsay MacDonald had been a widower for twelve years when he entered Number 10 as Prime Minister for the first time in 1924. He was a man of limited means compared to his predecessors, and purchasing linen and furniture for the house proved a financial strain. He did not have a private collection of paintings of his own and was obliged to borrow art from the National Gallery. Much to the disgust of some of his Labour colleagues he became a collector in later life. Socialist and social reformer, Beatrice Webb, observed in 1926 that he was ‘evidently absorbed in the social prestige of his ex-premiership, enhanced by a romantic personality,’ and that his love of fine art and furniture appeared to be accompanied by a growing interest in the company of grand ladies and gentlemen of ‘the enemy’s camp.’

The Breakfast Room and Official Dining Room in 1927

But diplomat, Harold Nicolson was struck by the fundamental simplicity of the man. ‘I observe a small figure in front of me with collar turned up,’ he recalled in his diary, ‘it is Ramsay MacDonald. We reach the door of Number 10. He knocks. The porter opens and stands to attention. Ramsay asks him…. ‘Is Ishbel in?’ ‘Yes, sir.’ ‘Would you ask her to bring two glasses to my room?’ We then go upstairs. The room has an unlived-in appearance. There’s a Turner over the fireplace. Ishbel [his daughter] is there. He asks her to get us a syphon. She says she can’t find any whisky. Ramsay says it is in the drawer of his table. He finds it. Malcolm [his son] comes in. ‘A cigarette?’ I say I will. ‘Malcolm goes to search for the Egyptian box. Then there are no matches… Ramsay… sees me out. Nothing will convince me that he is not fundamentally a simple man. Under all his affectation and vanity there is a core of real simplicity.’

First Floor Plan 1931.

The Prime Minister’s bedroom was on the first floor until the 1930s when the private residence moved to the second floor. Neville Chamberlain converted the room into a study, and his successors have followed his example by working in the same first floor office with its view over the garden, or in the Cabinet Room.