Many of the characters in To Kill A Tsar were real people, here are just a few of them.

Order

‘Alone in the utter solitude of his imperial state, surrounded by officials who were too often interested in deceiving him, disheartened by the apparent failure of his benevolent intentions, melancholy by natural temperament, and haunted for years by the ever present expectation of sudden and violent death, the life of the tsar has been a sad example of the gilded sorrow which may oppress the wearer of a crown.’

George Dobson, The Times, 14th March 1881.

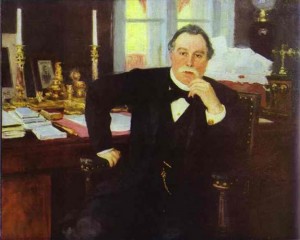

Tsar Alexander II [1818-81]

Tsar Alexander II

To Russia’s serfs he was the ‘tsar liberator’ who freed them from bondage to the estates of the aristocracy, but to those who dared call for representative democracy and an end to censorship he proved himself a tyrant. Handsome, sensitive, given to melancholy, the last years of his reign were blighted by the attempts on his life that turned him into a royal prisoner.

Count Vyacheslav Von Plehve [1846-1904]

A German-Russian lawyer, he served first as the prosecutor in St Petersburg then as Director of the Police Department, in which capacity he hunted down the few members of The People’s Will still at liberty after the assassination of the tsar. A ruthless conservative and anti-Semite, he was appointed Minister of the Interior in 1902 but was assassinated two years later when a revolutionary threw a bomb into his carriage.

Lord Dufferin [1826-1902], the British Ambassador

Lord Dufferin

A clever career diplomat who had already served as Governor General of Canada, he accepted the position of ambassador in St Petersburg in 1879 at a time of some rivalry between Britain and Russia in Asia and Afghanistan. He was popular at the imperial court and in St Petersburg society. He attended the Sunday parade at the manège on 1st March 1881 and spoke to the tsar just before his assassination.

Hariot Blackwood, Lady Dufferin [1843-1936]

Lady Dufferin

Like her husband, an Anglo-Irish aristocrat, she earned the reputation of the perfect diplomatic wife. During her time in Petersburg she kept a gossipy record of her life in high society, the imperial family, the embassy parties, bear hunts, the opera and ballet, and the activities of the revolutionaries: ‘I cannot tell you what a fearful impression it makes upon one, such cruel, persistent murder’.

George Dobson [1850-1938], The Times’ correspondent

For more than 25 years the newspaper’s man in the capital. He was a liberal and well informed commentator on the troubles of the empire and the growing threat of revolutionary upheaval. He reported the bomb attacks on the tsar and witnessed the eventual execution of the regicides. At the revolution in 1917, he was thrown into the Peter and Paul Fortress where many of the terrorists had been held, before being expelled from the country he regarded as his home.

REVOLUTION

‘On the one hand, the party declared that all methods were fair in the war with its antagonists, that here the end justified the means. At the same time it created a cult of dynamite and the revolver, and crowned the terrorist with a halo; murder and the scaffold acquired a magnetic charm and attraction for the youth of the land, and the weaker their nervous system, and the more oppressive the life around them, the greater was their exaltation at the thought of revolutionary terror.’

Vera Figner, executive committee, The People’s Will

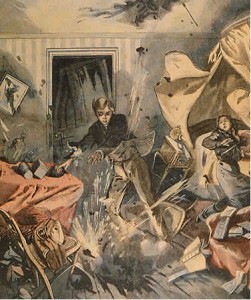

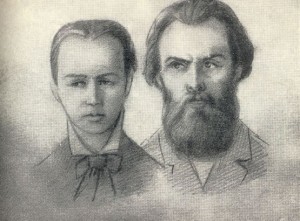

Sophia Pereovskaya [1854-81] and Andrei Zhelyabov [1850-81]

Perovskaya was from the Russian nobility; Zhelyabov the son of a house serf from the Crimea. Both became involved in agitation for democracy in the early 1870’s and were arrested and held for more than a year in prison before being acquitted. It was not until 1879 that they met properly for the first time, when, disillusioned with peaceful protest, they became comrades in The People’s Will, and then lovers. Zhelyabov was a charismatic figure, a leader of the group, who helped plan the assassination of the tsar. He was arrested a few days before the attempt and it was Perovskaya who led the bombers on March 1st. They died together on the scaffold.

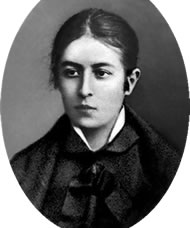

Vera Figner [1852-1942]

Vera Figner

‘The Venus of the Revolution’, famed for her beauty and her coolness and inner strength, she studied medicine in Zurich with her husband but divorced him to devote herself to political agitation. She was the only member of the executive committee of The People’s Will at liberty in Russia after the tsar’s assassination. She tried to carry on the group’s work, but was betrayed by an informer and arrested in 1883, and spent the next twenty years in prison, many of them in solitary confinement.

Alexander Mikhailov [1857-83]

Alexander Mikhailov

A gentleman revolutionary, he became active in student politics in St Petersburg, but gave up peaceful protest earlier than his comrades to found the ‘Death or Freedom’ group. He plotted the death of the head of the secret police in 1878 and helped Alexander Soloviev in his attempt on the tsar’s life the following year. A founder member of The People’s Will, he was in charge of internal security and played a leading part in its activities.

Geisa Gelfman [1855-82]

Geisa Gelfman

The daughter of a Jewish tradesman from near Kiev, she ran away from an arranged marriage at the age of 17 to train as a midwife. She was arrested for ‘propagandizing’ in 1875 and imprisoned for four years. Escaping in 1879, she joined The People’s Will and was involved in the plot to kill the tsar. Her lover, Nikolai Sablin shot himself when the police raided their apartment, and Gelfman was arrested, tried, and condemned to death, but spared the gallows because she was pregnant. She gave birth in prison and the baby was taken from her and sent to an orphanage. She died a few months later.

Nikolai Kibalchich [1853-81]

Nikolai Kibalchich

The son of a priest, he trained as an engineer but was arrested in 1875 for lending a prohibited book to a peasant. He spent three years in prison awaiting trial before being sentenced to two months. His chief passion was for rocketry rather than politics, but on his release he joined The People’s Will and became the group’s explosives expert. He made the bomb that killed the tsar. His bemused lawyer observed that he paid little attention to his trial but was ‘immersed in research on some aeronautic missile’. Hanged on 3rd April 1881 alongside Zhelyabov and Perovskaya, the design for his invention gathered dust in the police department for another thirty years. He is now celebrated as a pioneer of rocketry.

If you would like to know more on the reign of Tsar Alexander II and The People’s Will listen to the BBC In Our Time programme broadcast in January 2005.