Impatient with the failure of peaceful protest to bring political change in Russia, a group of revolutionaries met in the city of Lipetsk in the summer of 1879 to form a secret party to wage ‘intensive warfare’ on the government. The new party – ‘The People’s Will’ – was democratic and socialist in character, committed to an elected assembly and freedom of speech, but in pursuit of these ideals it was prepared to launch a terror campaign against the autocracy as embodied in the person of Tsar Alexander II.

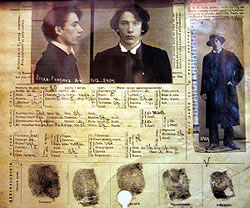

A File Held By The Secret Police On A Suspect

Its members took the sort of quasi monastic pledge an Al-Qaeda volunteer might recognise, to renounce love, ties of family and friendship, and to give their lives if necessary for the revolution. These demands ‘freed us from every petty or personal consideration’, executive committee member, Vera Figner wrote; ‘if they had not stirred one’s spirit so profoundly, they would not have satisfied us’.

Three months after its creation, it made its first unsuccessful attempt to kill the tsar by blowing up an imperial train outside Moscow. Then in February 1880 it succeeded in smuggling 300lbs of explosive into a cellar beneath the Winter Palace. The bomb was detonated as the tsar and his immediate family were preparing to take their places for dinner. They escaped unhurt but the attack shocked Europe, its crowned heads in particular: ‘Nerves are so taut that you expect to be blown up into the air at any moment’, the tsar’s brother observed; ‘we are living through the Terror’.

Tsar Alexander II is mortally wounded by the second explosion.

At no point did ‘The People’s Will’ number more than five hundred active members in Russia, its chief instrument – the executive committee – just twenty, but its organisation, its skilful use of propaganda and terror attacks placed it – in Karl Marx’s estimate – in ‘the vanguard of revolutionary action in Europe’. Its members were drawn from a wide cross section of Russian society. The party’s security chief, Alexander Mikhailov, was from the nobility; one of its leading lights, Sophia Perovskaya, was the daughter of the former governor general of St Petersburg. But most members belonged to the ‘raznochintsi’ – the ‘men of all ranks’ – the educated sons and daughters of priests, merchants, army officers, and even serfs. Women were particularly active in the party, in some cases rejecting husbands and families to join: ‘a man who admitted putting me above the cause, even in a moment of passion’, the revolutionary Ekaterina Obukova wrote in 1879, ‘would destroy everything that connected us’.

Like many terrorist groups since, the arrest and execution of its members by the authorities only served to spur those who remained to greater sacrifices, to avenge ‘the blood of our martyrs’, until sacrifice almost became the end in itself. The secret police were closing in on the senior figures still at liberty when the party’s executive committee authorised a final, suicidal, attempt on the tsar’s life. On the morning of 1st March 1881, Alexander II left the Winter Palace for the Sunday parade in Petersburg’s Manezhnaya Square. The terrorists had planted a large mine beneath a street close to the square but the tsar travelled by an alternative route. The terrorists had anticipated this might happen and a bombing party was waiting to move into place to intercept the tsar as he was returning to the palace. The first bomb exploded beneath the tsar’s carriage and he escaped unhurt, but minutes later a second was thrown at his feet mortally wounding him.

Within days, the leaders of the plot were in custody, and five of them were tried and publicly executed on 3rd April 1881. Did the death of Tsar Alexander II advance the cause of democracy? No. His son, Alexander III was determined to concede nothing to his father’s killers and his refusal to implement liberal reforms set Russia on the road to the revolution of 1917 and a new totalitarian state.

The body of Alexander II resting in state.