‘Your spies are here. My methodology has uncovered them,’ Anatoli Golitsyn intoned darkly, pointing his finger like the witch-finder at two files on the table in front of him.

From Spycatcher: The Candid Autobiography of a Senior Intelligence Officer, Peter Wright

Defectors, MI6 Chief Sir Maurice Oldfield observed, are like grapes; the first pressing is always the best. After days, perhaps weeks, of debriefing, when a defector has no more information to offer, he or she is put out to grass. The years of danger and excitement, of being feted by your chosen country, senior intelligence officers hanging on your every word, the money, the medals, all the accolades are over. Once squeezed a defector is nothing. Former KGB Major, Anatoli Golitsyn understood that very well, and that new Soviet arrivals would threaten his position as ‘expert’ of choice, so to protect it he kept up a flow of ‘intelligence’ for nearly ten years.

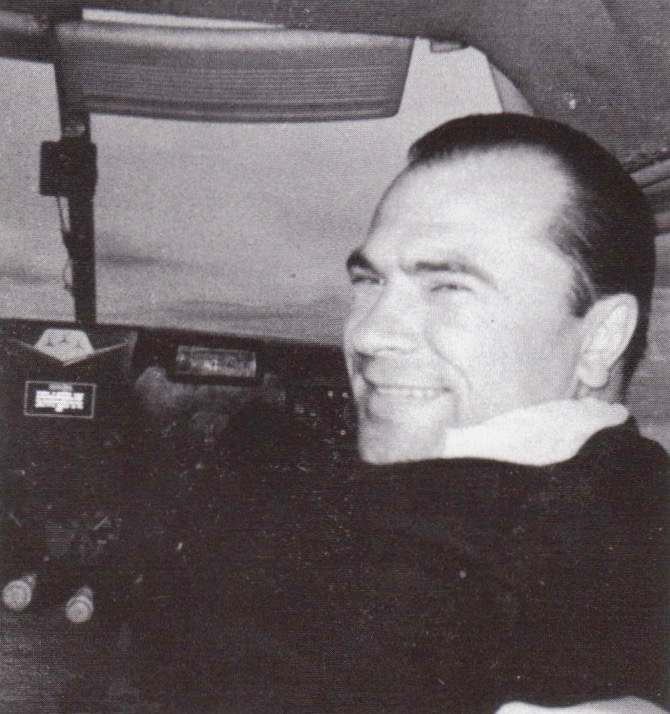

Ex-KGB Major Anatoli Golitsyn

It began in 1961 when he offered himself to the CIA and was interrogated by its counter-intelligence chief, James ‘Jim’ Angleton. He confirmed the existence of a ‘Ring of Five’ spies recruited in Britain in the 1930’s and provided intelligence that helped to identify Kim Philby as one of its members: First pressing most fruitful. Angleton declared him to be the most valuable defector to reach the West and rewarded him well for his contribution. Could he keep it up?

His answer was to invent a grand conspiracy. Golitsyn sought with ‘messianic zeal’ to persuade the Americans and the British that – in the words of MI5’s official historian – ‘they were falling victim to a vast KGB deception from which only he could save them’. The West was losing the Cold War because the Soviets had agents inside governments, intelligence agencies, the military – everywhere. The tentacles of the Soviet Octopus were reaching across the globe.

Former KGB Headquarters in Lubyanka

Golitsyn knew his story chimed with Jim Angleton’s own assessment of the Russian espionage threat to the United States. He was simply telling the counter-intelligence chief what he wanted to hear. ‘Both the CIA and FBI are doomed without my help’, he declared. Did he believe it? He may have done. One British intelligence officer who knew him described him as a ‘psychopath’ who believed he was a gift to the Western world.

But Angleton used Golitsyn to extend his own influence on both sides of the Atlantic. In 1963 he lent his pet defector to the spy catchers at MI5 to examine the files of those who might fit the profile of a KGB mole. During what Peter Wright called the ‘almost hysterical months of 1963’ Golitsyn encouraged the spy catchers’ belief that ‘treachery lingered in every corridor’, and like the witchfinders of the seventeenth century he pricked those he believed to be guilty, among them the Deputy Director General, Graham Mitchell. UB

Golitsyn was to exert a malign influence on British intelligence for almost a decade. In his book, Spycatcher, long-time disciple Peter Wright noted that the message was always the same: Golitsyn ‘laid special emphasis on Britain, and the many penetrations which, he claimed, were as yet undiscovered, and which only he could locate’.

Golitsyn was always able to count on his chief supporters, Angleton and Wright to make excuses for his mistakes because he served their purpose. When asked in 1965 why it had taken Golitsyn three years to come forward with a piece of intelligence, Angleton explained that he ‘was afraid of being laughed at’. For reasons still not clear, that seems to have been accepted as an adequate explanation because he was still helping MI5 with its investigations five years later.