The popular image of the spy catcher is of an elderly, tubby gentleman called George Smiley, well spoken, patient, dispassionate, with the ‘cunning of Satan and the conscience of a virgin’. Peter Wright was a very different character. He was a man of strong prejudice, contemptuous of many of the people he interviewed and resentful of his superiors. Was the master spy at the top of the British intelligence services the Director General of MI5, Roger Hollis, or his Deputy, Graham Mitchell? ‘I knew my choice would be based on prejudice’, he confessed in his memoirs.

Peter Wright’s memoir of the MI5 years

Wright admitted to a grudging respect for spies – ‘they had made their choice’ – but wrote disparagingly of the young idealists on the ‘periphery’ of the Communist Party who abandoned it when the crimes of the Soviet Union became widely known. He attacked the ‘Lotus Generation’ of 1930’s students who thought communism was a way to oppose Hitler and fascism everywhere. ‘Their cultured voices masked guilt and fear’, he wrote. ‘I had seen into the secret heart of the present Establishment at a time when they had been young and careless…. I knew too much, and they knew it.’ Many of those ‘young and careless’ students had abandoned communism at the outbreak of the Second World War and become pillars of the Establishment that Wright served and yet deeply resented, and he plainly enjoyed the power he was able to exercise over them in ‘defence of the realm’.

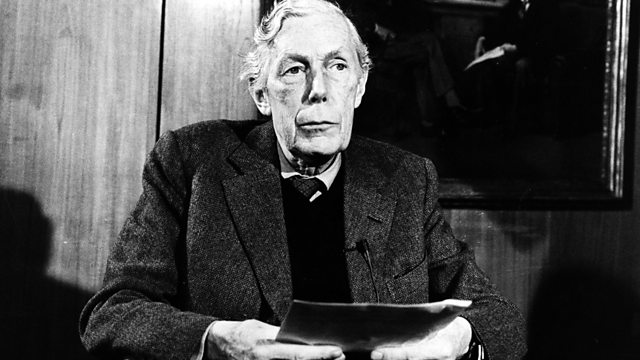

Anthony Blunt was a favourite subject. Surveyor of the Queen’s Pictures, Knight, respected academic, Blunt had been recruited at Cambridge in 1937. He confessed to spying for the Russians nearly thirty years later and agreed to co-operate in return for immunity from prosecution.

Anthony Blunt

Wright admired and was fascinated by Blunt and visited him for many years after his usefulness was exhausted. The relationship became an example of the strange symbiotic one that can develop between interrogator and interrogated, predator and prey. ‘Blunt was one of the most elegant, charming and cultivated men I have met’, wrote Wright; ‘The most striking thing about Blunt was the contradiction between his evident strength of character and his curious vulnerability. It was this contradiction which caused people of both sexes to fall in love with him.’

Ironically, it is a portrait of the spy catcher that emerges most vividly from his account of their meetings, of a man whose judgement was limited by his own experience. At one point he seems ready to hold Blunt accountable not only for spying but for the misfortunes that befell him as a child. Oh, I lived through it, Anthony’, he rails at Blunt, ‘I know more about the thirties probably than you will ever know. I remember my father driving himself mad with drink, because he couldn’t get a job. I remember losing my education, my world, everything.’

But after many years of secret life as a spy and a homosexual, Blunt was skilled at disguising his true feelings and at interpreting the motives of others. Wright’s predecessor, Arthur Martin, noted that Blunt would sometimes seem amused by his interrogations, and as Blunt’s biographer, Miranda Carter, observes, ‘it must have been a great temptation to play Wright, the man obsessed with a conspiracy which didn’t exist, who barely seemed to understand the difference between a fellow-traveller and a spy.’

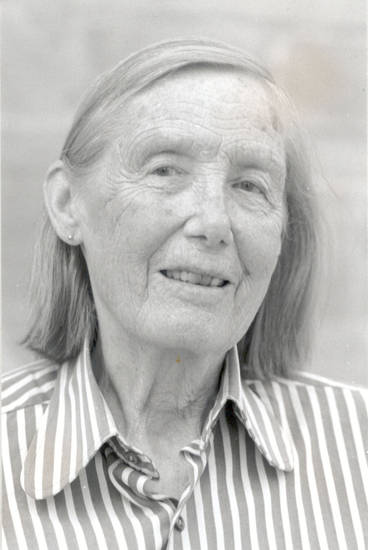

A fellow-traveller Wright expressed special contempt for was the Oxford academic, Jenifer Hart. ‘A fussy, middleclass woman’, he wrote, ‘too old for the fashionably short skirt and white net stockings she was wearing’, and he described her manner as ‘condescending’, ‘as if she equated my interest in the left wing politics of the 1930’s with looking up ladies’ skirts’.

Jenifer Hart

Hart was a member of Wright’s despised ‘Lotus Generation’. Upper middleclass, boarding school, Oxford University, an intellectual idealist, she joined the Communist Party in 1933 after working in one of its summer camps. When she left Oxford to become a civil servant, her comrades advised her to hide her Party membership. In her first months in post she met two communist contacts in secret, one of whom tried to recruit her as a Soviet agent. ‘I was told the Party would not expect me to do anything for ten years’, she wrote in her memoirs. ‘At first I was amused by the cloak-and-dagger atmosphere he generated, but I very soon felt uncomfortable and stopped meeting him.’ Hart claimed her contacts with the Party petered out, and by 1939 she had abandoned it altogether. She acknowledged later that she knew the Soviet regime was ‘authoritarian’ but, like many young communists at the time, she believed ‘a fairer social and economic system was more important than political democracy’. No one realised the extent of Stalin’s ‘great terror’, she argued.

Hart left the Civil Service in 1947 to become an academic at Oxford and when MI5 contacted her, nearly twenty years later, she readily agreed to co-operate. ‘I took the view that they [communists] could not be trusted’, she explained, ‘so I agreed to be interviewed’. Peter Wright showed her a long list of names and asked which of them were known to her. After the interview she ‘felt worried’, because Wright seemed ready to condemn her friends as communists purely through association with her.

Her meetings with Mr Wright were just the beginning of ‘a long and rather nasty affair’. Not long after, she was removed from the Civil Service Final Selection Board, then versions of her story began to appear in books and newspapers. For the rest of her life she struggled to shake off claims that she had passed secrets to the Russians. She always denied it, but Wright didn’t believe her, what’s more, he was willing to tell journalist contacts so.