‘As you know, gentleman, an election is due’, Peter Wright remembered the Director General of MI5 observing to some of his senior officers in October 1964, ‘better for the Service if we can resolve this case now, so that I do not have to brief any incoming Prime Minister’. The Prime Minister he had in mind was the leader of the Labour Party, Harold Wilson. ‘Everyone knew what he meant’, Wright recalled.

Prime Minister Harold Wilson with American President Lyndon Johnson

The British intelligence services have always had a troubled relationship with the Left. Thirty years after the fall of the Berlin Wall allegations of Labour ‘treachery’ during the Cold War still make the front pages of Britain’s conservative newspapers. The most recent was in The Mail on Sunday which reported in May 2019 that files in a Czech government archive suggested veteran Labour MP and former Cabinet minister, Geoffrey Robinson, passed secrets to its intelligence service between 1966 and 1969. Robinson denied passing any information to a Czech ‘handler’ or even that he had access to government secrets at the time. The reports, he said, were simply a ‘lie’ https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-48324690

A similar allegation was levelled at Labour Party leader, Jeremy Corbyn in 2018. The source was another file in a Czech communist era archive. It included reports of meetings in the 1980’s between Corbyn and a Third Secretary at the Czechoslovak Embassy in London. The suggestion in some papers was that the Leader of Her Majesty’s Official Opposition had passed information to a Soviet Bloc spy: The BBC uncovered a very different story https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-europe-43168245. According to its reporter the Labour MP gave the Third Secretary nothing except a photocopy of a newspaper article, and there was no evidence to suggest Czech intelligence regarded him as anything other than a potential source.

Corbyn and Robinson are just the latest Labour Party politicians to be accused of acting as agents, ‘agents of influence’ or ‘confidential contacts’. Much has been made of contacts between British left wingers and Eastern Bloc ‘diplomats’ during the Cold War. The British agent, KGB Colonel Oleg Gordievsky reported to handlers in the early 1980’s that there was a file in Moscow Centre on another Labour Party leader, Michael Foot, code name BOOT, and that he had accepted money for information. The Sunday Times printed the allegations in 1995, Foot sued and won damages for ‘a McCarthyite smear’. But the charge has not gone away. The journalist, Ben Macintyre claimed in his book The Spy and the Traitor, https://www.theguardian.com/politics/2018/sep/15/labour-figures-slam-claim-that-michael-foot-was-paid-by-soviets that the KGB made payments to Foot of £1,500, a sum equivalent to £37,000 today, and that the money was probably used to prop up the left-wing Tribune newspaper.

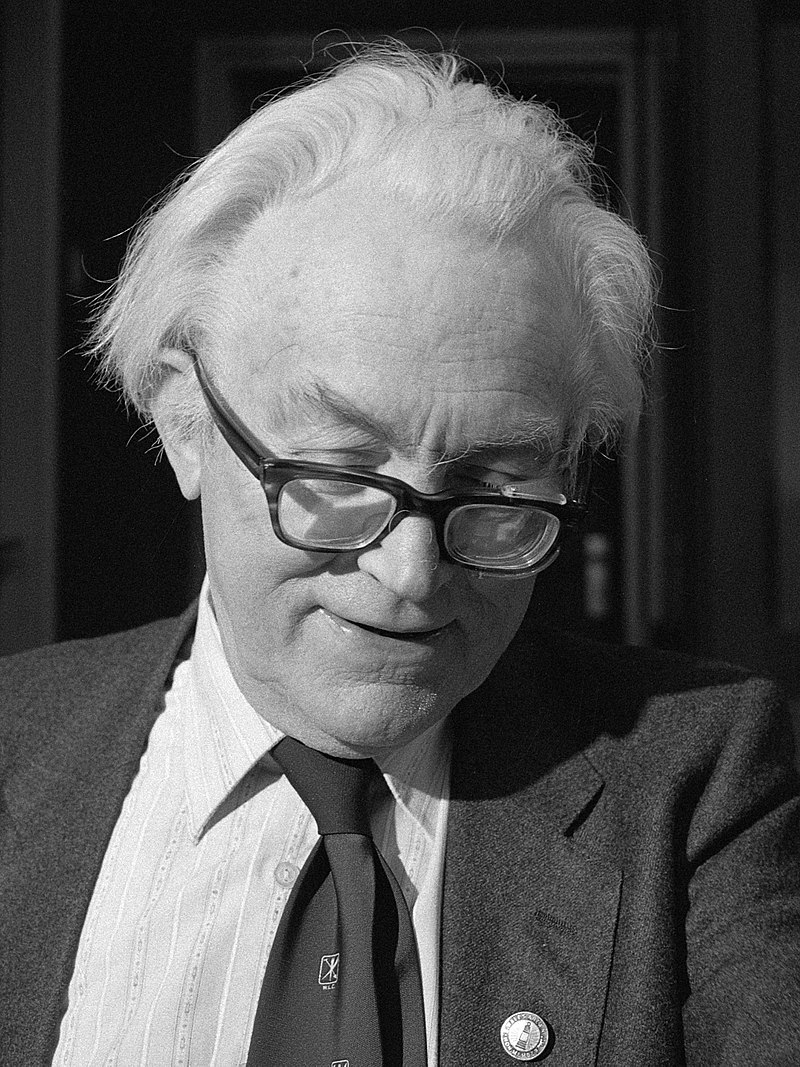

Michael Foot

Foot believed it was his duty to understand what was happening behind the iron curtain and reach across it with the hand of friendship. The British intelligence services naturally viewed any approach to or from the other side with suspicion, especially if money was changing hands. But Foot did not hide his contacts with Eastern Bloc ‘diplomats’, he was critical of Moscow, he leaked no state secrets and he did not break the law. Macintyre suggests elsewhere in his book that the KGB in London exaggerated its contacts and that much of the information it sent to Moscow in the early 1980’s was ‘pure invention’. The Eastern Bloc intelligence services regarded Britain as a plumb posting. To hold on to a position in one of the London embassies it was important to point to successes. Not easy – there were very few. Gordievsky reported to his handlers at MI6 that Soviet penetration of the British Establishment was ‘pitiful’ and that ‘paper agents’ were kept ‘on the books’ so that KGB officers in London appeared busy. The Director General of MI5 reported in the 1980’s that Michael Foot was once a KGB agent; the Cabinet Secretary considered the evidence carefully and very wisely decided not to take it to Prime Minister.

For most of their history the British intelligence services have been deeply conservative bodies, much more comfortable with governments of the Right than the Left. From the first days of the Soviet Union senior officers harboured the suspicion that socialist was another word for communist. And the suspicion was mutual, born of the Zinoviev affair, when in 1924 the heads of both intelligence services played a part in bringing down the first ever Labour Government. Their instrument was a fake letter purporting to be from the head of the Communist International in Moscow calling on Party members to engage in seditious activities to bring about a British revolution. Rightly or wrongly, senior Labour figures blamed publication of the letter in The Daily Mail for their general election defeat a few days later.

The Zinoviev affair rankled with Labour for years. When Ramsay MacDonald was returned to Downing Street in 1929, he refused to be in the same room as one of his intelligence chiefs and business had to be conducted through an intermediary. Seventy years later the new Labour Government of Tony Blair was exercised enough by the Zinoviev Affair to commission a fresh inquiry into the role of the intelligence services.

Zinoviev is remembered by the Left; the many instances of communist infiltration generally forgotten. Of the 393 Labour MPs elected to parliament in the landslide victory of 1945, a dozen were secret communists. Four of them were eventually expelled from the Labour Party, another fifteen were on a watch list marked for possible expulsion. In 1961 Labour leader, Hugh Gaitskell, authorised a secret approach to MI5 for information on members of the parliamentary party. A list of sixteen Labour MPs the leadership believed were ‘under Communist Party direction’ was shared with its Deputy Director General. Top of the list was the Honourable Member for Morpeth, Will Owen, who was later exposed as an agent of the Czechoslovak intelligence service.

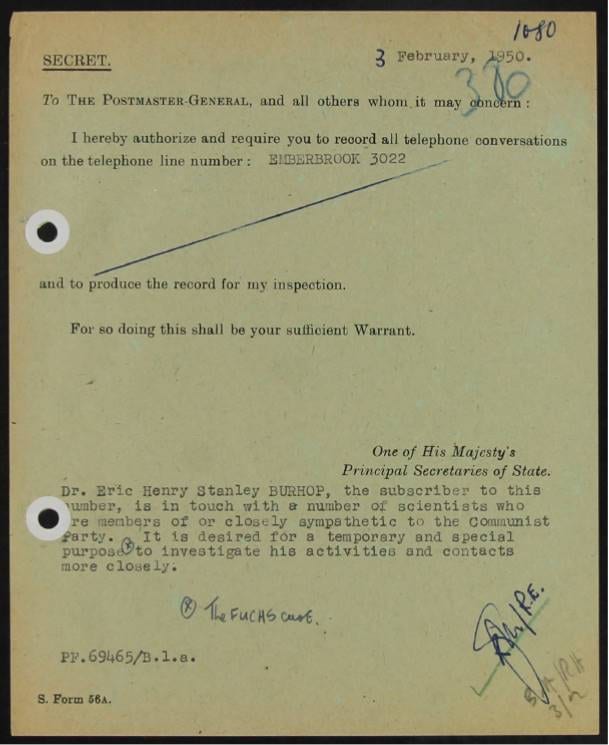

MI5 wiretap form

Another on the list appears as a character in Witchfinder: Tom Driberg was a notorious gossip and roue – for many years a society columnist – who loved hearing people’s confidences but enjoyed sharing them with others even more. His reputation went before him, and yet he has been accused not only of spying for the KGB and the Czech security service but of supplying MI5 with information. In truth there is no evidence Driberg revealed more to handlers on either side than he was prepared to share with journalists in a Fleet Street wine bar. Peter Wright conceded as much. ‘For a while we ran Driberg’, he recalled, ‘but apart from picking up a mass of salacious detail about Labour Party peccadilloes, he had nothing of interest for us’.

Wright and his colleagues investigated a number of Labour MPs in the 1960’s who were known to have been members of the Communist Party when they were young. Defence Secretary Denis Healey refused to answer their questions; MP Bernard Floud made the mistake of giving the spy catchers a chance. Wright and a colleague ‘interrogated’ him robustly and finally declared him to be a ‘full security risk’. A short time later Floud committed suicide. The death of his wife was certainly a factor in his decision to take his own life, but MI5 historian, Christopher Andrew, has written that failure to gain security clearance and the subsequent collapse of his ministerial ambitions ‘probably added to his despair’. ‘MI5 was terrified that it would be publicly linked’, Wright remembered, and did its best to cover up the circumstances surrounding his death.

Floud was a casualty of the ‘enemy within’ hysteria that gripped British and American intelligence services in the sixties when a cabal of counterintelligence officers embarked on the witch hunt that is the subject of my story. The head of counterintelligence at the CIA, James Angleton, was to have a profound influence on Wright and his colleagues at MI5.

James Angleton

The former assistant chief of Canadian counterintelligence, James Bennett recalled a revealing discussion in Washington about the communist ‘threat’ with Angleton and his deputy, Ray Rocca. As was often the case at informal gatherings of intelligence officers in the sixties, a great deal of alcohol was consumed and tempers became frayed. Working class Welshman by birth, Bennett had at one time been a staunch supporter of the Labour Party and he was shocked by the ignorance of the Americans and their stubborn refusal to acknowledge a difference between communism and socialism and social democracy. All ‘Reds’, seemed to be their attitude, with only a difference in the shade. The argument became so heated Rocca threw a punch at Bennett. That night clearly left a lasting impression on the participants because four years later Angleton opened a file on Bennett. It was the first step in a process that ended with him being hounded out of Canadian counterintelligence at the behest of the CIA. ‘My life has been destroyed’, Bennett confided to his diary in 1972. ‘What more do they want of me? May God forgive them.’

Angleton’s disciples in MI5 shared his hostility to all shades of ‘Red’ whether they were democratically elected or not. A few months after that drunken evening in Washington in 1964, Labour won a General Election and Harold Wilson became Prime Minister. ‘When I was posted to the London station’, one of Angleton’s CIA colleagues recalled, ‘I simply could not believe my ears when I heard the openly scurrilous and disloyal remarks MI5 officers made about their Prime Minister. You would never hear CIA officers talking like that in front of foreigners about the President of the United States.’

Prime Minister Harold Wilson on the steps of Number 10

Unbeknownst to the new Prime Minister MI5 had opened a file on him after the Second World War with details of his contacts with communists and of his business trips to the Soviet Union. Because of its sensitivity it was held under the pseudonym ‘Norman John Worthington’. Wilson was under surveillance for a time in the 1950’s, and material was gathered on the background of his associates. Interest quickened in 1963 when he was elected leader of the Labour Party, an event that was to occasion one of the most bizarre investigations in the history of British intelligence.

Its genesis was hearsay ‘intelligence’ from the CIA’s pet defector, Anatoli Golitsyn. The ex-KGB Major claimed a colleague in Moscow had told him of a plot to assassinate ‘a Western opposition leader’ and replace him with someone more sympathetic. The mysterious death of Harold Wilson’s predecessor seemed to fit the profile. Hugh Gaitskell had died of a rare autoimmune disease called Lupus erythematosus. Was he infected by the KGB? Golitsyn thought so, and his word was enough to persuade MI5 and the CIA to open an investigation. The motive was clear: Gaitskell was a Labour right winger, committed to the retention of Britain’s nuclear deterrent, Wilson a ‘left winger’ – or so it seemed then – sympathetic to Moscow. The KGB had helped its ‘agent of influence’ to the top job. Wright claimed later that the investigation began because one of Gaitskell’s doctors was disturbed by the manner of his death and suspected foul play. There is no evidence to support this version of events. What is clear is that senior officers in both MI5 and the CIA viewed the Prime Minister of Great Britain as a Soviet ‘agent’ who was working against the interests of his country and the West. Twenty years later, Peter Wright was unrepentant. ‘Harold Wilson is a wrong ‘un’, he observed to an interviewer, and Angleton continued to tell his CIA colleagues the same.

Harold Wilson with Soviet leaders, Brezhnev and Gromyko on a visit to Moscow

Wilson knew nothing of the WORTHINGTON file and the investigation of Gaitskell’s death, but he was convinced the intelligence services were out to get him. Ten years after entering Downing Street as Prime Minister for the first time, he was returned in another general election. Sitting in his study at Number 10 on his first day back he remarked to a friend, ‘There are only three people listening – you, me, and MI5’. By the time he left Office he was holding impromptu discussions with associates in the lavatories of Number 10 with the taps on to prevent imaginary bugs in the ceiling picking up the conversation.

For years Wilson’s colleagues assumed he was suffering from the sort of spy paranoia that infected the minds of Wright and Angleton, but it now seems clear he had good reason to be suspicious. A file seen by Five’s historian, Christopher Andrew, is understood to have contained details of an operation to monitor conversations in Number 10. Bugs were placed in the Cabinet room, the waiting room and the Prime Minister’s study at the request of Harold Macmillan in July 1963, and they remained there until 1977. They were finally removed on the orders of the then Prime Minister, Jim Callaghan, who made a disingenuous statement to MPs denying that electronic surveillance had ever been undertaken in Downing Street. The intelligence contained in the file was suppressed by MI5. Whether Wilson was told his conversations were being monitored isn’t clear, but his behaviour certainly demonstrates the lack of trust that has always existed between Labour and the British intelligence services.